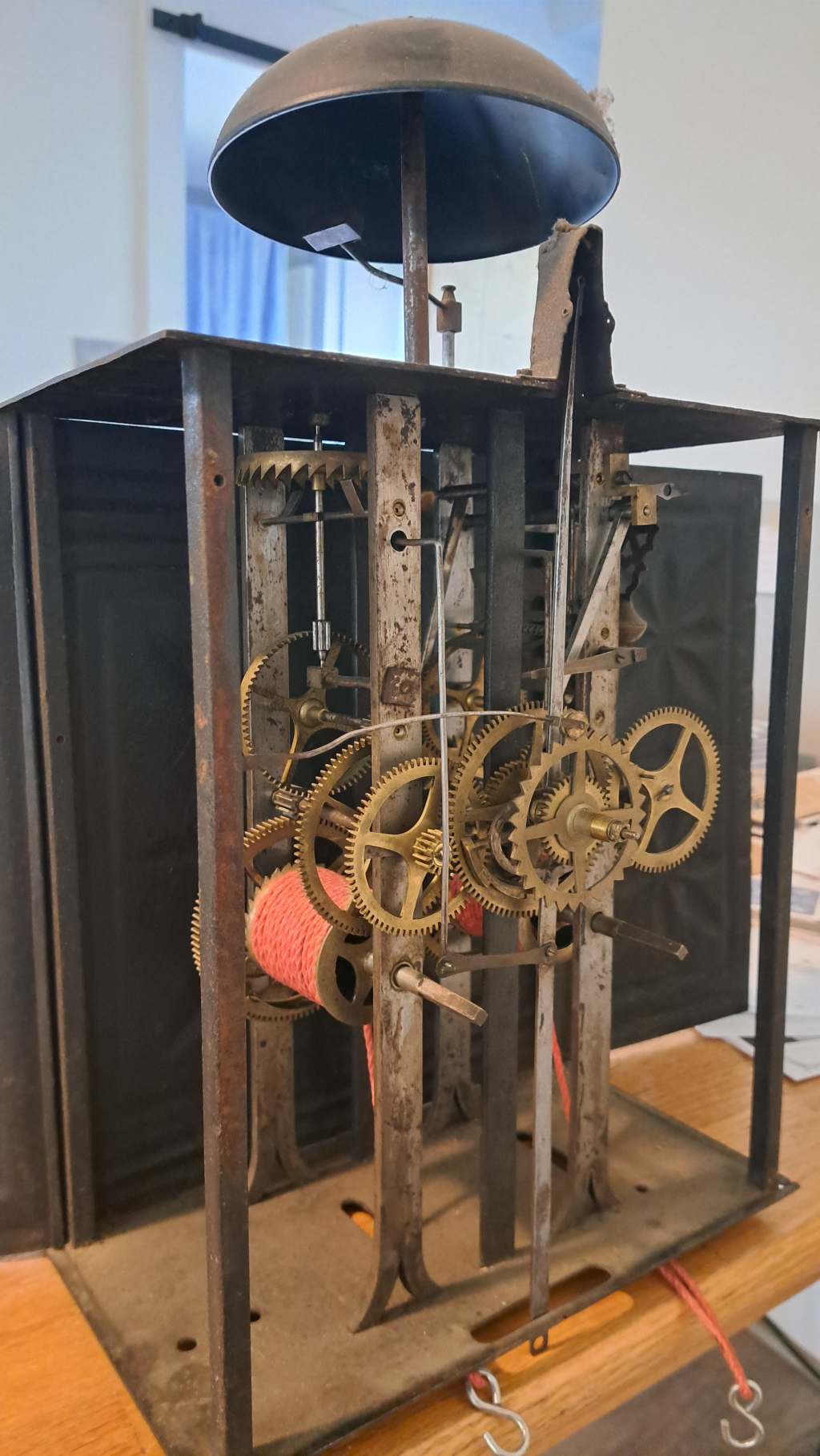

This is a french Comtoise or Morbier clock with a crown wheel escapement. Also known as a verge escapement, this form of controlling the release of energy is the earliest known type of escapement, and the one used for the longest time, supplanted in the early to mid 19th century by the anchor escapement.

Here’s our first look at it:

The main issue I found is that the string meant to suspend the pendulum is broken.

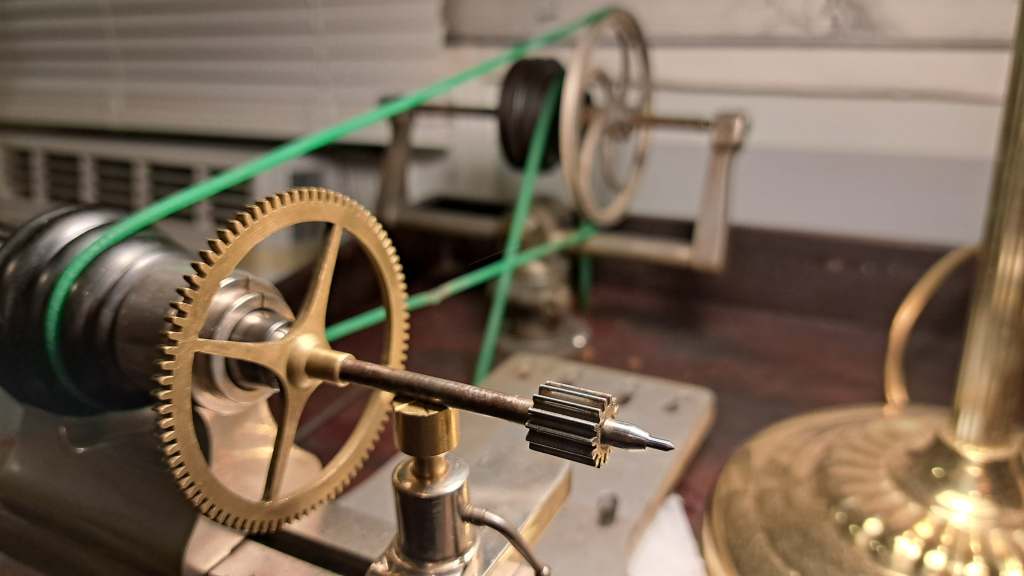

I disassembled the whole thing and cleaned all the parts. Then I polished all the pivots on a watchmakers lathe (pictured below), and smoothed the pivot holes with smoothing broaches (not pictured).

Next I re-bushed the worn pivot holes. I think there was just one or two on the time-side.

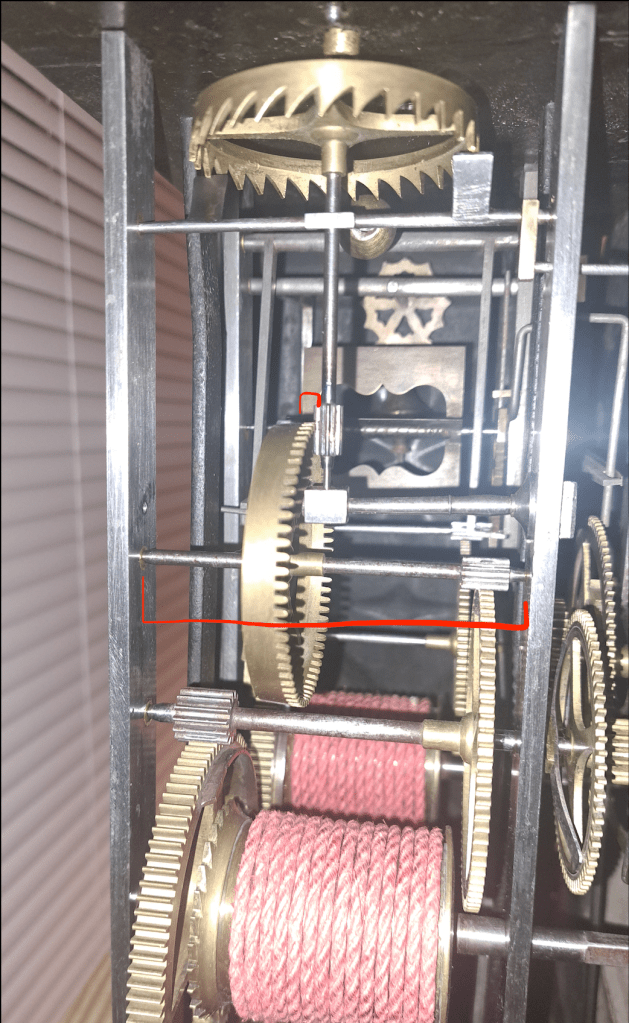

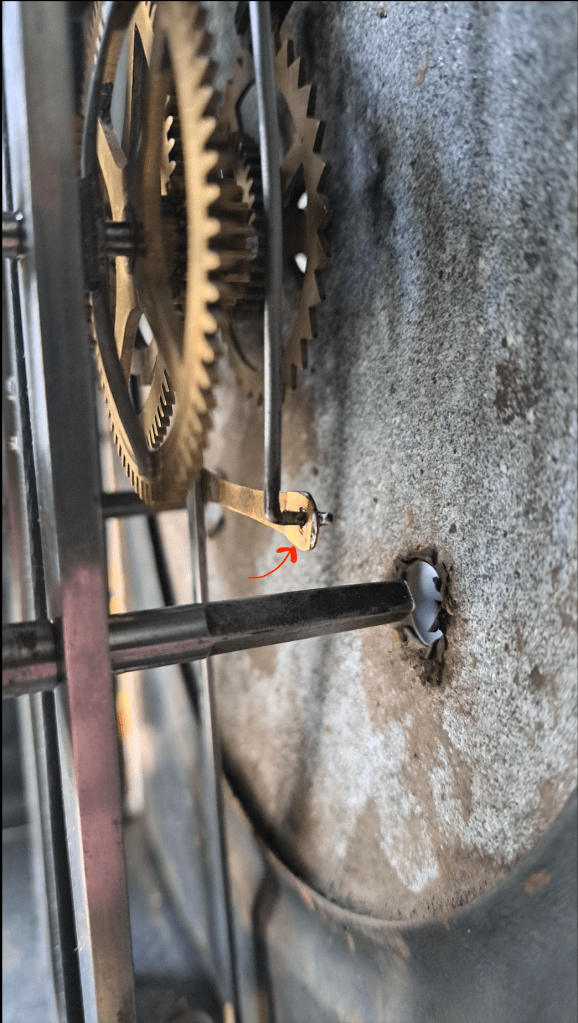

Here’s our first up-close look at the crown wheel and verge escapement. The crown wheel is the spiky one at the top. The verge is the horizontal rod (or in latin virga) that interacts with the spiky wheel. As you can see, the crown wheel arbor is riding quite loose in its bushings, causing a wobble that we’ll need to fix.

I fixed the wobble by re-bushing both the upper and lower bushings the crown wheel arbor sits in. The pictures below capture some of the steps involved:

Now the crown wheel has no wobble:

With those sorted I turned my attention to the verge pallets: the surfaces that interact with the spikes of the crown wheel. They had some wear on them in the form of gouges. I polished them out:

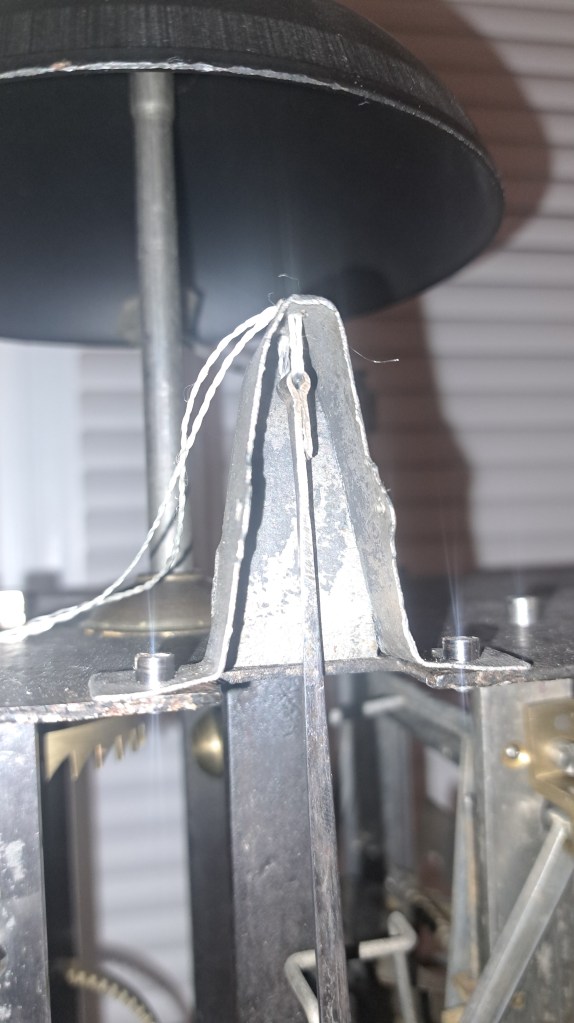

Next I replaced the string holding the pendulum up:

Now I adjusted the escapement to have a nice tick-tock and transfer of energy into the pendulum. This was quite a finicky process of adjusting the height of the crown wheel relative to the pallets. I did this both by re-bushing the verge and by moving the bottom bushing holding the crown wheel up or down in its post – setting the height.

Another problem arose in the depth of engagement between the contrate wheel and the crown wheel pinion. After much testing I found that I was loosing some power to friction between the contrate and pinion because they would slowly drift apart while the clock was running. To remedy this I affixed a thin flat spring to the back post holding the contrate wheel bushing and arbor. This prevented the contrate wheel from backing away from the crown wheel pinion.

Now we have a better-adjusted escapement. I write better because it was very difficult to get it perfect. I did not want to shave down the pallets too much, so I’m accepting a little more drop on one than the other. It runs well, in any event.

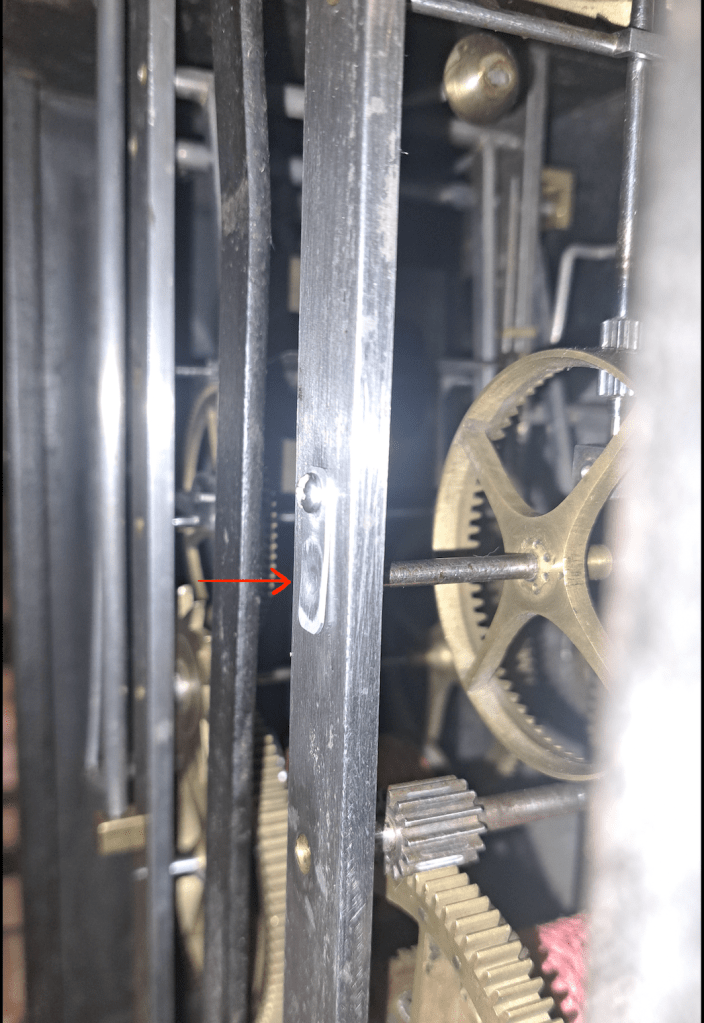

I kept having power issues though. It seemed the mechanism just wouldn’t push the pendulum enough. I tried adjusting the escapement so there was virtually no drop at all. I even tried lots of drop, out of desperation. One area where I noticed I was losing some power was in the crutch rod linkage. In the photo below you can see I added on a bit of brass to make the linkage’s hole smaller and hopefully not lose any motion. This probably did help, but was not enough to keep the clock running more than 15 minutes.

Eventually I turned to forums and discovered that it is a known fact these crown wheel escapement comtoise clocks need a smaller, lighter pendulum than the typical french lyre pendulum this clock came to me with! So I made a pendulum using a rod and a wooden bob I turned on a lathe. To my great relief it now runs! What I think happened is someone moved this clock at some point, lost the pendulum, and just wanted to have some pendulum inside so that it would look right.

I gave it a final oiling

Now for the coolest feature of these clocks, the double strike:

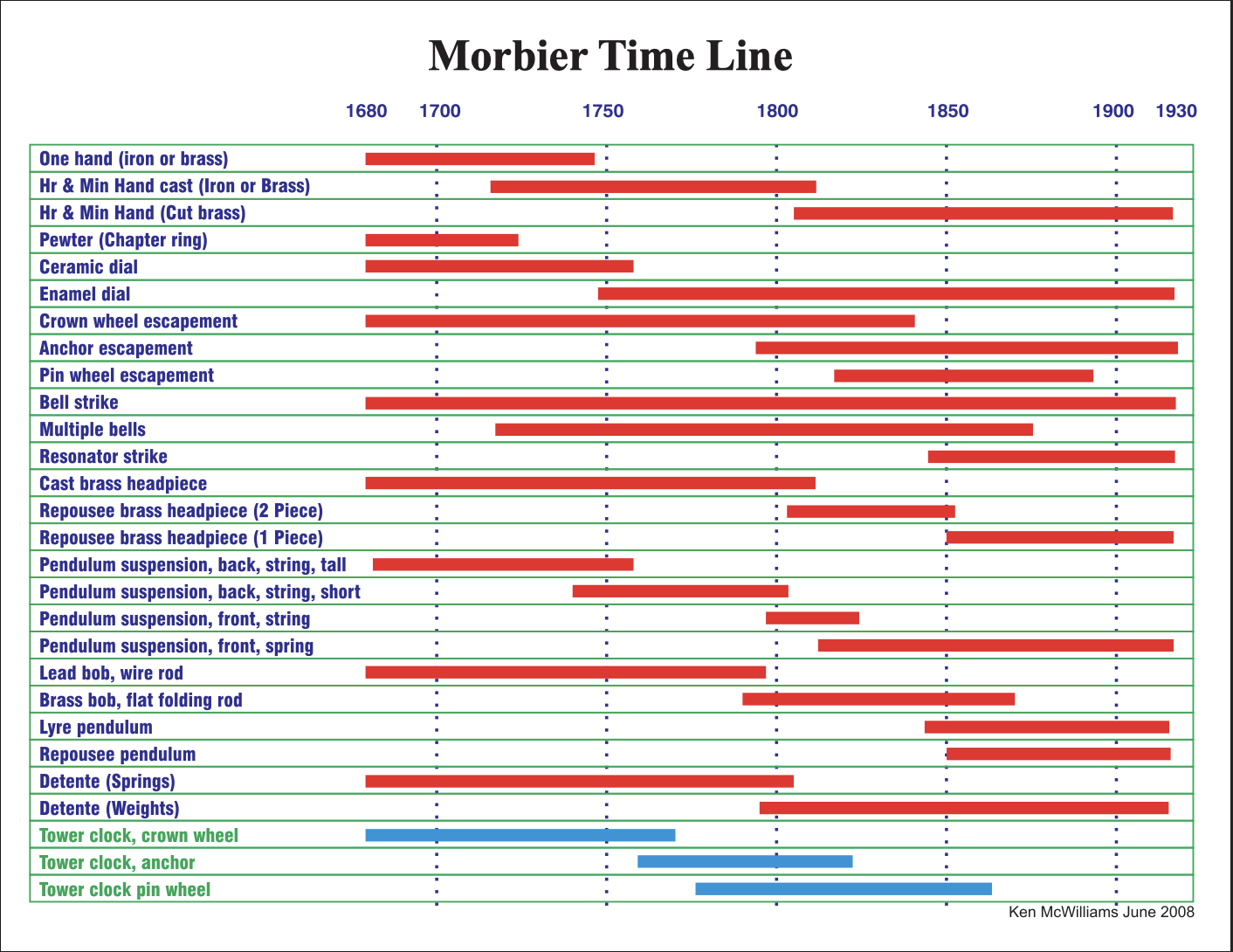

This clock features: a crown wheel escapement; Pendulum suspension, front, string; and Detente (Weights). Using the chart above, I date this clocks to be between 1795 and 1815. The 1 piece repousee brass headpiece may suggest it is more towards the latter end of that spectrum, but due to some unused mounting holes, it is possible the headpiece was a later addition, or that the movement was made to accept multiple kinds of headpieces. This is based on “A Guide to Dating Morbier Clocks” by Ken McWilliams: https://www.nawcc-ch190.com/datingmorbiers.pdf.

[Below is copied from my previous blog post about a comtoise clock]

About the name… Comtoise literally refers to the region of Franche-Comté in eastern France, bordering Switzerland. Another name these clocks go under is Morbier, a village in the area. How did these geographical names come to refer to these mechanical objects? The answer is that geography plays a role in shaping the ambit of human activity.

More generally referred to as the Jura region (due to the Jura mountains), this area has long been involved in the production of clocks, watches, and music boxes.

A number of reasons led to this: firstly, the climate. While the weather and land supports farming in the summer, harsher winters prompted farmers to seek supplemental means of income. This led to household cottage industries popping up in the winter months.

While the natural landscape provided the time and workforce, the political landscape shaped the content of the industry. The border between France and Switzerland was a busy one during the Protestant Reformation (starting around the 1520’s) and into the 18th century in France as Huguenots (French Protestants) fled persecution and settled in Protestant-friendly Switzerland. Huguenots were often involved in the burgeoning commercial and capitalist ventures in urban centers and as such many were skilled tradespeople with an interest in new technology. Again many factors led to the Huguenot predilection for skilled crafts like clock and watchmaking, but I think an important element is what sociologist Max Weber called the “Protestant Work Ethic,” where individual hard work and worldly success was prized as a sign of salvation. In any event, as Hugenouts fled Paris and other French cities for Geneva and Bern, often settling near the border in the Jura region, they brought with them knowledge of clock and watchmaking and an appetite to start industries.

We may probe the political geography further, and see that in a way it may be another feature of the physical geography. Why did France, with its politics, end here, and Switzerland, with its other politics, begin there? Why did two different (yet similar enough to share migrants and markets) cultures take root in the first place? The short answer is the Jura mountains and other aspects of the natural landscape that formed a border separating groups of people. This reveals little about the intricacies of why one culture ended up one way and the other another, and really geographical determinism can easily be taken too far and be unproductively reductive (if interested, here’s a video). I think its better to think of the way geography encourages and discourages certain human activities, but those activities always remain very human and thus highly contingent on the agency of people and “society.”

In any event, a cottage industry was born in the 16th to 19th century that saw farmers in the Franche-Comté area construct and assemble clock movements in the winter. Usually they just built the movements, selling them to others who would distribute them to retailers. These retailers would be the ones to case the movements. This arrangement begins to explain the “Comberousse” and “à Bourgoin” written on the dial of our clock. Comberousse could have been the name of a retailer or shop in the central French commune of Burgundy.

Leave a comment