This is what’s known as a Comtoise or Morbier grandfather clock. Let’s clean it up and get it ticking again, then we can discuss its name.

Someone repainted the case. My instructor and I began to scrape the paint away, but that process is still ongoing.

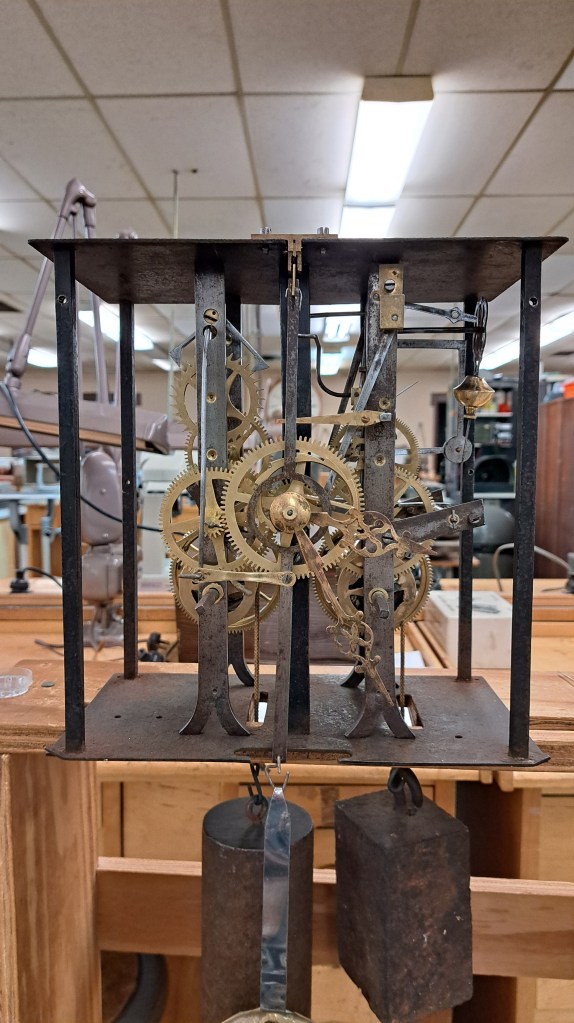

Here’s our first look at the movement.

With a nice iron frame it’s built like a tower clock.

First I disassembled it. The upright posts had tabs that fit into slots in the cage. While these posts are iron, they have brass bushings for the pivot holes. Note also the punch marks at the bottom of the posts; likely made by the original maker, these help us keep track of which posts go where.

Then I gave everything a good clean. It’s getting its shine back!

I burnished all the pivots.

While doing that I noticed I’m not the first to give this clock some love and care. Someone replaced some teeth on the above wheel by cutting out a dovetail shape, soldering in a new piece, and filing in new teeth profiles. I have a post about that process here.

Then I smoothed the pivot holes. This clock was really in good condition for being around 200 years old – the pivots and pivot holes were all still in-round.

The biggest issue is that the barrel which holds the cable for the weight was working itself loose from one of its end caps. The previous repairer had obviously re-soldered it. I did the same, trying to get a better connection this time.

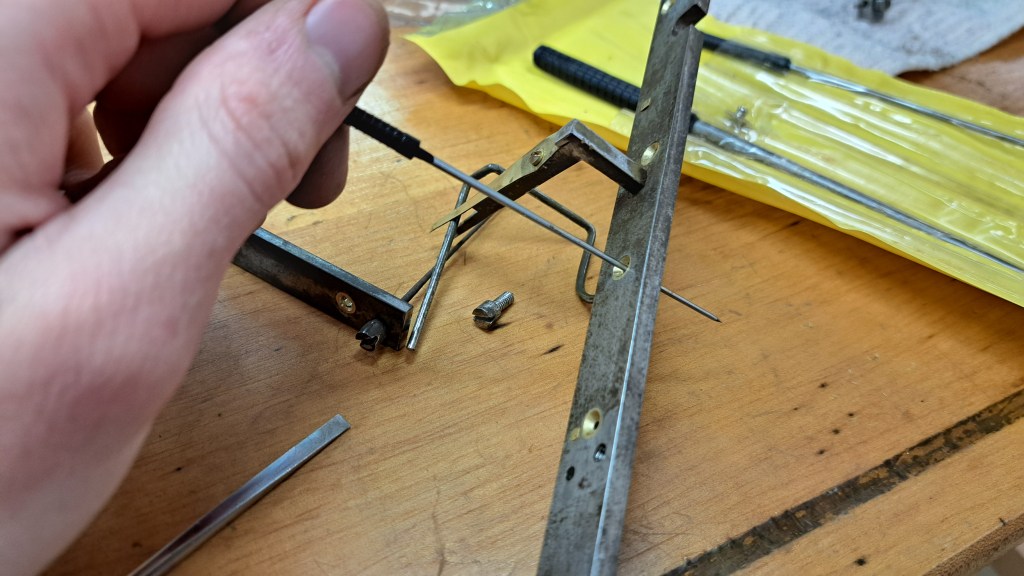

Now to address the escapement. The pallets had a bit of wear.

This is to be expected and indicates the clock has lived a good working life. Let’s extend that life by polishing out the wear.

Then I checked just the geometry of the escapement, adjusting it to get a nice even “tick tock.”

And putting it all back together! I wish I had taken a video of it back in it’s case and striking. As is typical with these clocks, it strikes the hour, then strikes the hour again a minute or two after the hour – just in case you missed it the first time!

Now about the name… Comtoise literally refers to the region of Franche-Comté in eastern France, bordering Switzerland. Another name these clocks go under is Morbier, a village in the area. How did these geographical names come to refer to these mechanical objects? The answer is that geography plays a role in shaping the ambit of human activity.

More generally referred to as the Jura region (due to the Jura mountains), this area has long been involved in the production of clocks, watches, and music boxes.

A number of reasons led to this: firstly, the climate. While the weather and land supports farming in the summer, harsher winters prompted farmers to seek supplemental means of income. This led to household cottage industries popping up in the winter months.

While the natural landscape provided the time and workforce, the political landscape shaped the content of the industry. The border between France and Switzerland was a busy one during the Protestant Reformation (starting around the 1520’s) and into the 18th century in France as Huguenots (French Protestants) fled persecution and settled in Protestant-friendly Switzerland. Huguenots were often involved in the burgeoning commercial and capitalist ventures in urban centers and as such many were skilled tradespeople with an interest in new technology. Again many factors led to the Huguenot predilection for skilled crafts like clock and watchmaking, but I think an important element is what sociologist Max Weber called the “Protestant Work Ethic,” where individual hard work and worldly success was prized as a sign of salvation. In any event, as Hugenouts fled Paris and other French cities for Geneva and Bern, often settling near the border in the Jura region, they brought with them knowledge of clock and watchmaking and an appetite to start industries.

We may probe the political geography further, and see that in a way it may be another feature of the physical geography. Why did France, with its politics, end here, and Switzerland, with its other politics, begin there? Why did two different (yet similar enough to share migrants and markets) cultures take root in the first place? The short answer is the Jura mountains and other aspects of the natural landscape that formed a border separating groups of people. This reveals little about the intricacies of why one culture ended up one way and the other another, and really geographical determinism can easily be taken too far and be unproductively reductive (if interested, here’s a video). I think its better to think of the way geography encourages and discourages certain human activities, but those activities always remain very human and thus highly contingent on the agency of people and “society.”

In any event, a cottage industry was born in the 16th to 19th century that saw farmers in the Franche-Comté area construct and assemble clock movements in the winter. Usually they just built the movements, selling them to others who would distribute them to retailers. These retailers would be the ones to case the movements. This arrangement begins to explain the “Lizée” and “à Avranches” written on the dial of our clock. Lizée was likely the name of a retailer or shop in the northwestern French commune of Avranches. I have been unable to track down any details about this Lizée.

I think this clock is from the early to mid nineteenth century. From what I’ve seen, the anchor escapement places this clock no earlier than around 1790, and the pendulum suspension spring housing being in the front of the clock also indicates not much earlier than 1815. This is based on “A Guide to Dating Morbier Clocks” by Ken McWilliams: https://www.nawcc-ch190.com/datingmorbiers.pdf.

[Please let me know if any of this history is incorrect! If I had more time I would look into these books (not the rat one, though…)]

Leave a comment