“I wasted time, and now doth time waste me;

For now hath time made me his numb’ring clock.” (Richard II, Act V, scene v)

Here is a statue clock with a visible Brocot escapement. After servicing it I’ll discuss this combination of such an exposed mechanism with a casting of Shakespeare into a “numb’ring clock.”

I started by removing the movement from its case.

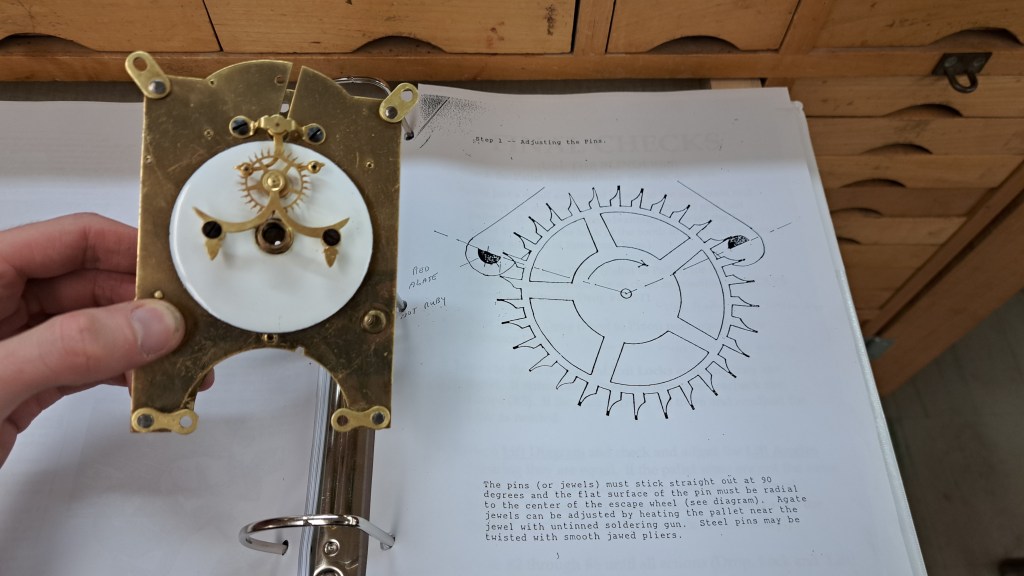

Here’s a closer look at the visible Brocot escapement on the dial.

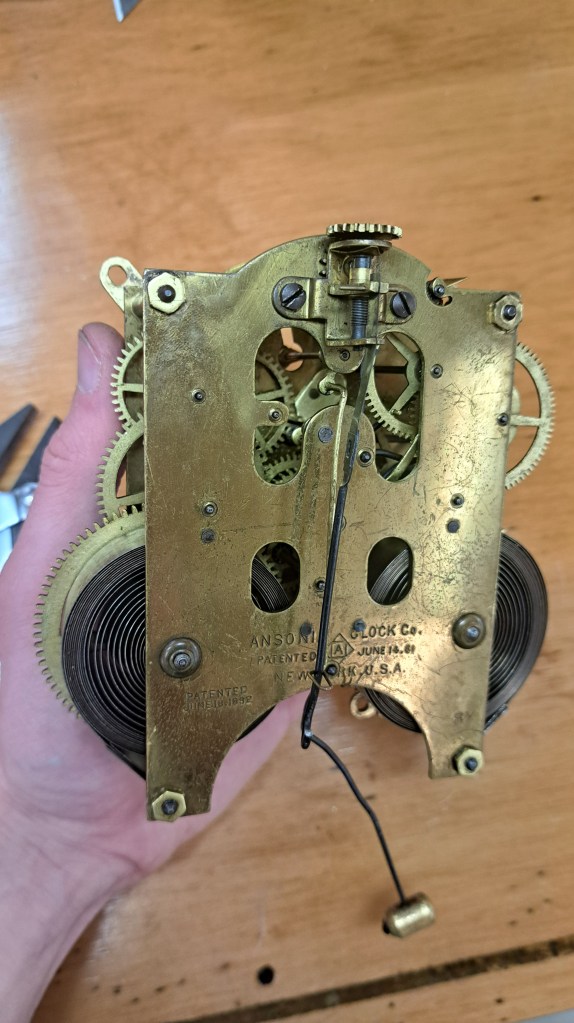

Here’s the back of the movement. Note the device at the top of the plate which holds the suspension spring. With a screw, it can be minutely adjusted to move the pendulum up and down to regulate the clock from the dial – this makes regulating much easier. It is also called a Brocot Suspension.

After putting clamps on the mainsprings and letting the power down, I took off the back plate to investigate the entrails within.

Here’s all the parts laid out, and then being put into an ultrasonic bath for cleaning.

After cleaning and drying I turned my attention to the pivots and pivot holes: the parts that receive most of the wear as the clock runs. [I forgot to take a picture, but I also cleaned and properly re-lubricated the mainsprings.]

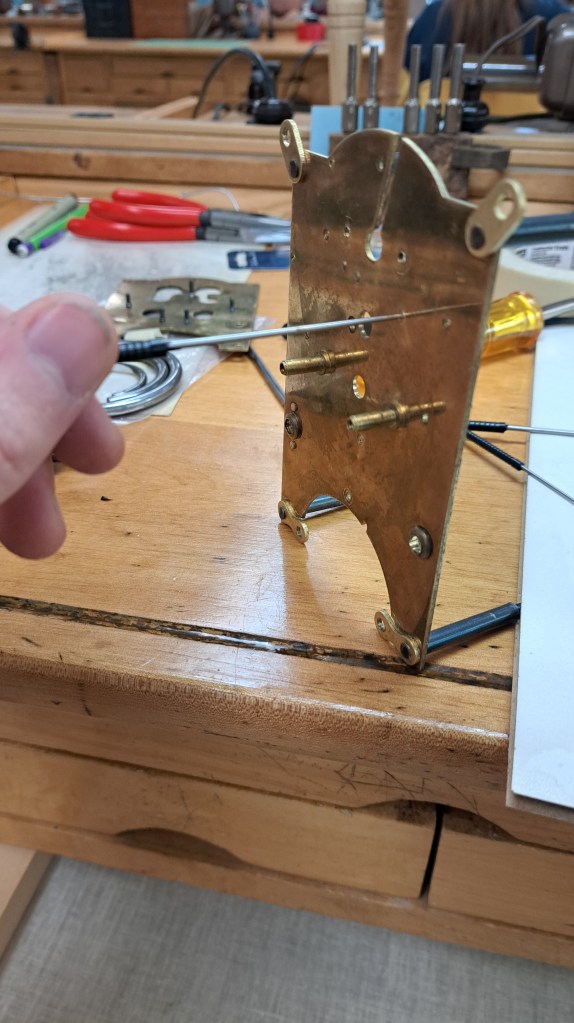

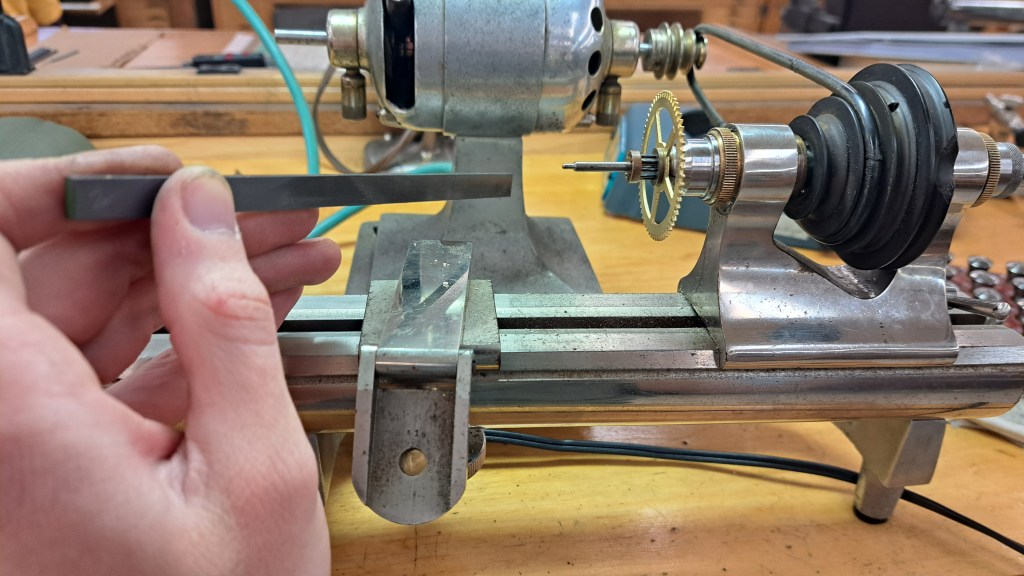

The pivot holes just needed smoothing with a smoothing broach (pictured above), and I burnished all the pivots to likewise be smooth (below).

Then I turned my attention to the escapement anchor and pallets, which on this clock are a real showpiece as they are exposed on the face of the dial for all to see. The Brocot escapement was invented by the Frenchman Louis Gabriel Brocot (1791-1872) and improved by his son Louis Achille (1817-1878), who then also invented the suspension mentioned earlier (and developed a number tree). Other than looking good, I also find it to be very easy to adjust and get running well.

The pins are held in with shellac which can just be heated with a lamp to soften. Then the pins can be adjusted so that the geometry is ideal.

After testing the escapement I reassembled the whole movement and tested the strike function.

Then I mounted the movement back in its Shakespearean case.

Shakespeare occasionally used a clock in a metaphor, or spoke of the strike of the clock to signpost the plot in a play, but I think he is mainly a random figure to attach to a clock. One of certain, though mostly perfunctory, refinement and sophistication, used to elevate those of the clock’s owner.

I will try, though, to suggest two reasons the pairing of this clock mechanism with a statue of Shakespeare can be apt.

First, taking the mechanism in light of Shakespeare, the mundane, cyclical movement of the hands becomes a scene to spectate. The hands play their parts, on cue with the stage orchestra in the pit below (the striking on the hour). And then there is the Brocot escapement front and center, the pallets engaged in a dialogue, going back and forth, driving the play forward. And even though we’ve seen this one before, it’s a classic! (also, schoolchildren find both Shakespeare and analog clock faces tricky texts to analyze…)

Finally, taking the Bard in the light of the clock, the playwright is rendered as a great dead yet immortal figure. He sits there, never to move again, but though time so visibly and invariably passes we still know who he is. The statue thus acts as a static counter to the fleeting minutes of the hands; one tells of change, the other of a legacy that will not fade. It’s uncertain who has bested whom: has Shakespeare’s fame put time in check? Or is the cold, unmoving form of the statue another reminder that time and death strike all?

“When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night,

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls all silvered o’er with white:

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd

And summer’s green all girded up in sheaves

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard:

Then of thy beauty do I question make

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake,

And die as fast as they see others grow,

And nothing ’gainst Time’s scythe can make defence

Save breed to brave him, when he takes thee hence.” (Sonnet 12)

Leave a comment